When you hold a leadership position, the timing of your speech can be just as crucial as the content. Despite relying on data, logic, reasoning, and analysis, our inherently social nature plays a significant role. Our innate desire to harmonize and collaborate persists. So, how can the least experienced individual in your organization feel at ease expressing dissent with the most seasoned professional?

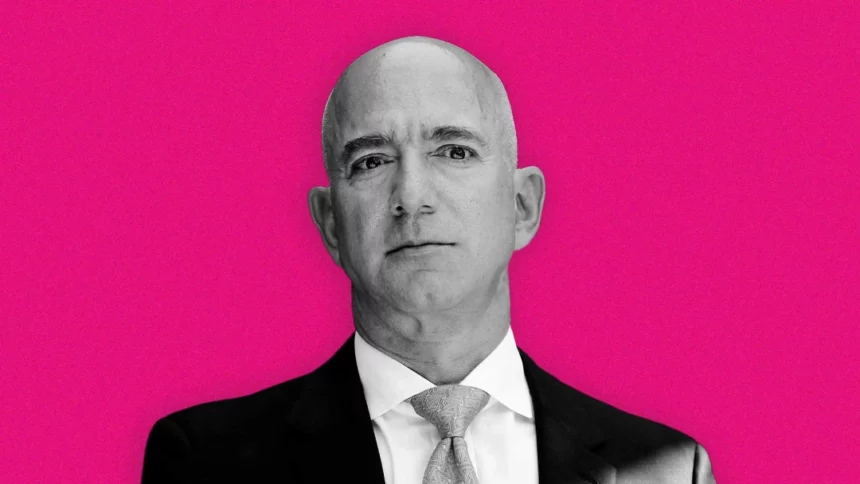

As recently conveyed by Jeff Bezos on the Lex Fridman podcast:

In every meeting I attend, I always speak last. I know, from experience, if I speak first, even very strong-willed, highly intelligent, high-judgment participants in that meeting will wonder, “If Jeff thinks that? I came into this meeting thinking one thing, but maybe I’m not right.” If you’re the most senior person in the room, go last. Let everyone else go first. Ideally, have the most junior person go first — try to go in order of seniority — so that you can hear everyone’s opinion in an unfiltered way. Someone you really respect says something? It makes you change your mind a little.

Jeff Bezos

When you possess an idea, or more specifically, when you believe you hold the solution—even if you refrain from explicitly stating that viewpoint—it becomes effortless to pose leading, constraining questions. It’s simple to frame questions that presuppose a particular answer.

In such instances, it becomes uncomplicated to disregard others’ input when there’s a preconceived notion of being correct. As articulated by Simon Sinek:

The skill to hold your opinions to yourself until everyone has spoken does two things: One, it gives everybody else the feeling that they have been heard. It gives everyone else the ability to feel that they have contributed. Two, you get the benefit of hearing what everybody else has to think before you render your opinion. The skill is really to keep your opinions to yourself.

Simon Sinek

Agreeing with scientific research, a 2013 study in Science discovered that initial opinions significantly influence later viewpoints, leading to what researchers call “accumulated herding.” Also, a 1998 study in the Journal of Risk and Uncertainty found that one person’s opinion, especially a “senior” figure, has a large impact on final decisions, creating what social scientists term an “informational cascade” that triggers similar opinions.

To promote effective communication, follow these guidelines:

- Keep your questions short and simple, asking in one or two sentences to stay open-ended. For instance, ask, “How can we boost productivity?” or “How can we enhance quality?” to avoid leading questions.

- Hold off on suggesting options initially, saving your ideas for when it’s your turn to speak. Recognize the slim chance of having thought of every possibility.

- Stick to clarifying questions without passing judgment until it’s your turn to contribute. Avoid dismissing ideas too early, as the first expression of doubt may hinder meaningful input.

- Speak last to create a welcoming environment for diverse viewpoints. Your main goal is to uncover what others know, so focus on listening attentively to gather valuable insights.