Artificial Intelligence (AI) poses a significant challenge to the labour landscape. Its impact could range from being a manageable issue to one of existential importance, akin to the transformative effects of industrialization or globalization. Before delving into debates about AI’s effects on workers, it’s crucial to frame the discussion correctly. This isn’t merely a clash between a traditional labour movement and technological advancement; rather, it’s a question of how the wealth and efficiency gains generated by AI will be distributed.

It’s tempting to view today’s workers grappling with the encroachment of AI as the latest chapter in an age-old story. They are likened to the mythical Luddites, smashing looms due to ignorance; the artisans displaced by the advent of factories, or even the horse-and-buggy drivers resistant to embracing automobiles. From a capitalistic perspective, this narrative portrays technological change as a natural progression toward advancement, driven by savvy businesspeople who reshape society for greater efficiency and reap the rewards of their ingenuity.

Workers are often depicted as unfortunate casualties of capitalism’s inherent cycle of creative destruction. While it’s understandable that they fear change, their self-interest is often dismissed. According to this narrative, true leadership involves maximizing overall productivity, even if it means condemning certain segments of the workforce to poverty. This narrative, championed by neoliberalism, continues to shape our reality.

However, like most fairy tales, this story contains both truths and deceptions. It’s true that workers across various industries, such as media, marketing, law, and transportation, are apprehensive about the implications of AI for their livelihoods. This uncertainty stems from the unpredictable nature of AI’s capabilities and the certainty that employers will utilize it to replace human workers. Hollywood writers and actors staged strikes last year, driven largely by this pragmatic assessment. While the exact impact of AI remains unclear, the consensus is that companies will prioritize their interests at the expense of workers if left unchecked.

In my industry of journalism, the distinction between “AI as a tool to enhance journalists’ work” and “AI as a cheap, unethical substitute for human journalists” hinges on whether labour power can influence companies to make ethical choices. In industries lacking robust unions, government regulation may be the only recourse to ensure responsible AI implementation. Regardless, the time for action is now. According to the International Monetary Fund, 40% of the global workforce is poised to be affected by AI—a fact that warrants justified apprehension.

Working people and the labour movement must craft a different narrative—one grounded in pragmatic realism and genuine concern for humanity, qualities often absent in the business world. While it’s challenging to halt the spread of productivity-boosting technological advancements like AI, organized labour can advocate for equitable distribution of the gains it generates. The internet, globalization, and ride-hailing apps exemplify how difficult it is to impede technological progress.

Capitalism ensures that technologies enhancing productivity proliferate rapidly, and AI is no exception. Unions can play a crucial role in ensuring that AI deployment is not haphazard or exploitative. However, the primary battle lies in ensuring that the economic, efficiency, and productivity gains brought about by AI benefit workers rather than accruing solely to management and investors.

Consider a scenario where AI enables a company to achieve the same output with half the workforce in half the time. In one scenario, the company lays off half its workers, slashes labour costs, doubles productivity, and funnels all profits to investors and executives. In another scenario, displaced workers are retrained for other roles or provided with generous severance packages and training for new careers. The remaining workers enjoy reduced work hours with maintained pay, and profits are shared among the workforce through profit sharing or employee ownership.

In the first scenario, AI exacerbates inequality and job insecurity. In the second scenario, it fosters equitable distribution of gains and improved working conditions. It’s still early in AI’s development, and both paths are open for consideration.

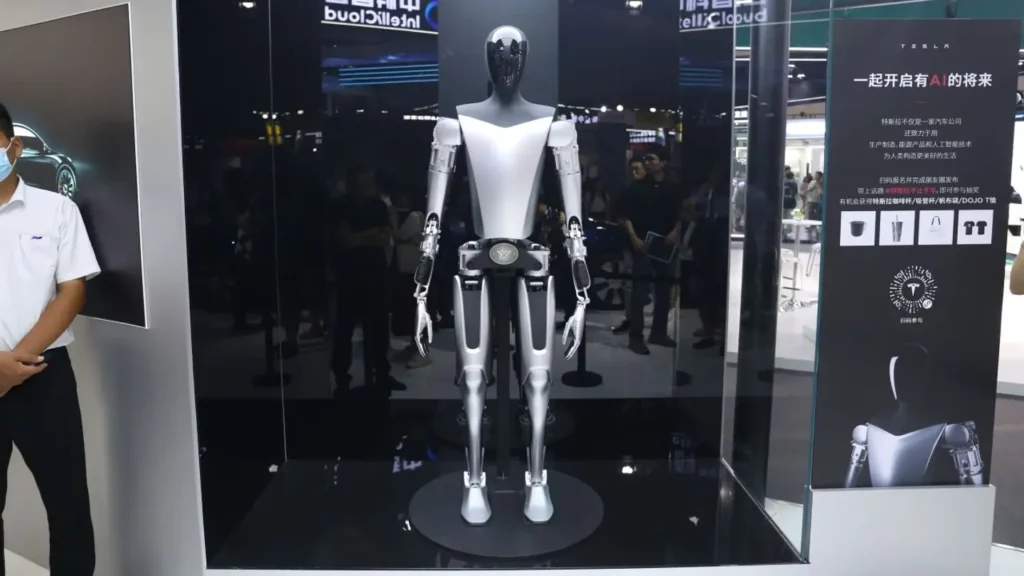

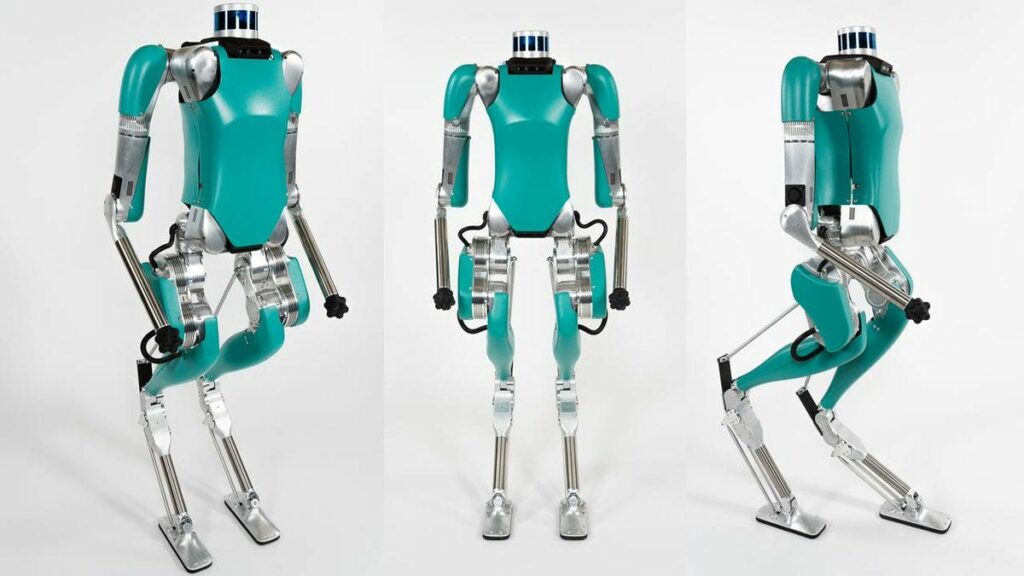

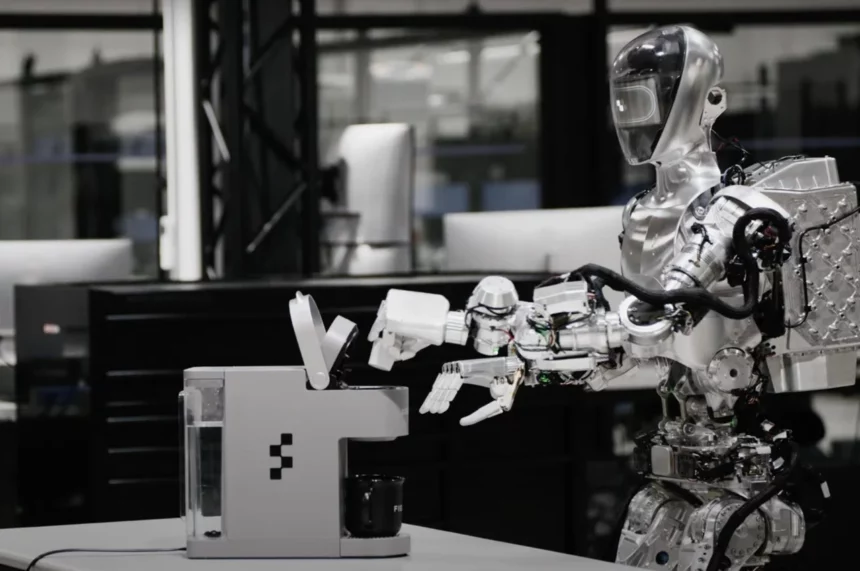

This represents the crux of the issue. When Hollywood screenwriters protest against AI-generated scripts or hospitality workers caution against the pitfalls of robotic baristas, they are not ignorant of the potential productivity gains of AI. Instead, they recognize that without their intervention, these gains will disproportionately benefit the top echelons, leaving workers with little to show.

Beware of those who, having profited from AI, portray workers as backward opponents of technology. This narrative echoes the flawed economic theories that heralded globalized free trade as universally beneficial while ignoring its unequal distribution of gains. This debate transcends technology; it’s a matter of political economics. Will automation liberate us from menial labour and enhance our lives, or will it exacerbate job losses and increase hardship for millions?

If AI proves to be a reality, it should be treated as a public good rather than a private one. While unions may not prevent AI’s integration into industries, they can advocate for its benefits to be shared equitably.

Every business operates by converting labour into profit, which is then distributed among workers, managers, and investors. If technological advancements like AI boost profits while reducing labour, workers have a rightful claim to those gains over other stakeholders. The disgruntled horse-and-buggy drivers would be less resistant if they knew they had a future in driving modern trucks. Technology should serve people, not the other way around.