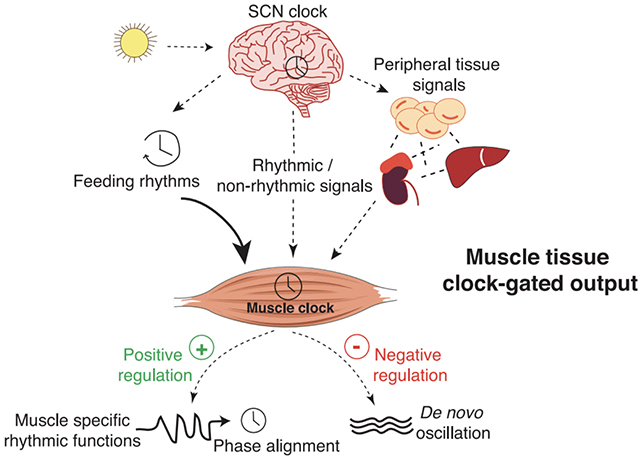

We rely on several biological clocks to synchronize our bodies internally and with the outside world. Recent studies highlight how these clocks collaborate to maintain tissue function and slow down ageing. The research delves into the central circadian clock, managed by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the brain, and the peripheral circadian clocks found throughout the body. These clocks regulate the timing of cellular processes in organs, muscles, and skin.

As long as the central clock communicates with a peripheral clock during the day, crucial processes such as DNA repair, mitochondrial activity, metabolism, and the natural cell cycle remain on schedule. Exploring and potentially controlling these mechanisms in greater detail could represent a significant advancement in maintaining overall health and slowing the ageing process as we grow older.

“Our study reveals that minimal interaction between only two tissue clocks, one central and the other peripheral, is needed to maintain optimal functioning of tissues like muscles and skin and to avoid their deterioration and ageing,” says biologist Pura Muñoz-Cánoves, from the Pompeu Fabra University in Spain at the time of the research.

The research encompasses two complementary studies published concurrently. The first, featured in Science, utilized experiments with mice to demonstrate how restoring coordination between brain and muscle clocks protects against muscle wastage and loss of muscle strength and function.

In the second study, published in Cell Stem Cell, the team investigated the circadian clock in the skin of mice. Once again, this clock depended on the central clock for proper operation; without this regulation, crucial functions like DNA replication occurred at inappropriate times.

Despite this, the peripheral clocks exhibited some autonomy, the research revealed. They could still track 24-hour cycles and oversee a small fraction of cell functions. Furthermore, restricting the feeding times of the mice to specific periods of the day, in the absence of the brain clock, was shown to aid peripheral clocks in better self-management.

“It is fascinating to see how synchronization between the brain and peripheral circadian clocks plays a critical role in skin and muscle health, while peripheral clocks alone are autonomous in carrying out the most basic tissue functions,” says Aznar Benitah from the Institute for Research in Biomedicine Barcelona in Spain.

The circadian rhythms that unfold in our bodies over 24 hours are pivotal to most biological processes, including sleep and digestion. When they’re disrupted – with jet lag or night shifts, for instance – negative health impacts can ensue. Understanding this timekeeping is crucial to comprehending health.

While muscles, skin, and the central nervous system all deteriorate with advancing age, the researchers behind these two studies believe that their work has the potential to preserve physical performance later in life. “The next step is to identify the signalling factors involved in this interaction, with potential therapeutic applications in mind,” says Muñoz-Cánoves.

The research has been published in Science and Cell Stem Cell.