As the dream of home ownership becomes further out of reach for many younger Britons, Generation Rent is facing an entirely new challenge. For young professionals living in cities such as London, the economics of owning a car no longer make sense.

“It is getting harder and harder to own a car and it is becoming harder and harder to run,” says Andrew Smith, managing director of Sixt, the vehicle rental company. Driving is on a path to becoming “fundamentally different,” says Smith. Soon, instead of owning cars, people will share them, he adds. “I very much see that as being the future.”

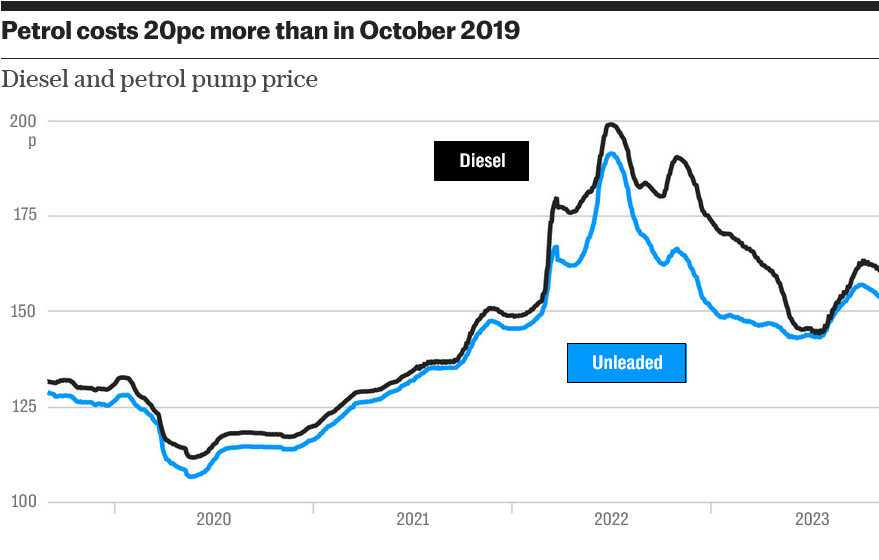

Nearly a third of motorists are driving less often in a bid to curb spending since the cost of living crisis began, according to a survey by Sixt. More than half consider owning a car to be a financial burden. “Drivers are currently under the cosh from record high motoring costs,” says AA president Edmund King. Petrol pump prices are up by a fifth compared to October 2019.

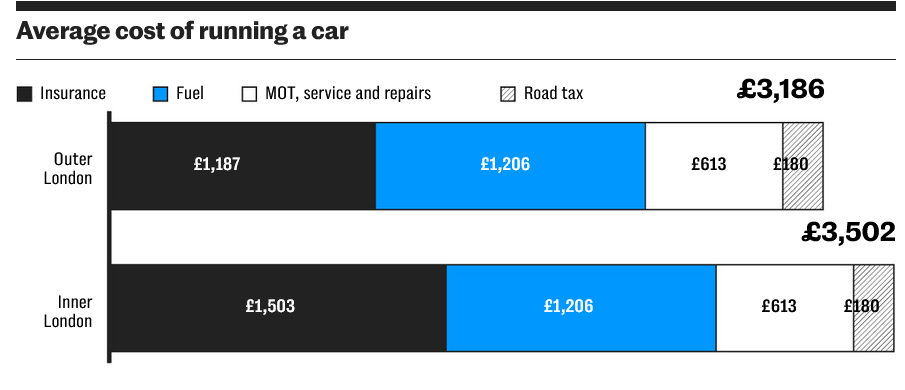

Car insurance premiums have surged by 29pc in the last 12 months to hit an all-time high of £561, as materials and labour shortages drive up the cost of work, according to the Association of British Insurers. The AA has warned that some insurers are removing windscreen cover in a bid to offer cheaper policies.

The upfront costs of purchasing a car have also climbed. Second-hand car prices rocketed during the pandemic supply chain crisis when chip shortages hit the delivery of new vehicles, and they have not returned to normal levels. Since August 2021, data from AA Cars shows the price of a second-hand Toyota Aygos has jumped by 16pc, with a Vauxhall Corsa up by 12pc and a VW Polo 8pc more expensive.

“Normally only classic or collectable cars increase in value,” says King. In London, many drivers have also been hit by the Ultra Low Emission Zone (Ulez) expansion, announced in November last year. Many motorists have already sold their cars as a result. “We see customers now who come to us every Friday and rent a car just for the weekend, to get out to the country, maybe to visit a second home, or catch up with family outside of London,” says Smith. “They are saying, ‘Actually this is a far more economic way of living’.”

Drivers are also turning to months-long car subscriptions, instead of leasing a car, says Smith. “We are seeing a still small but fast-growing pool of customers who say ‘I’ve got a three-month work project. I will take a car for three months rather than buying an asset and hoping the project extends,” he adds. Sixt’s subscription service is small, but growing rapidly. In October, bookings were up by 329pc year-on-year.

Young professionals are at the heart of the transition. “They don’t have the same attachment to ownership. They would rather not shell out high capital costs for an asset that gets used very infrequently,” says Smith. Younger people are also more likely to be renting flats that have no parking spaces, he adds.

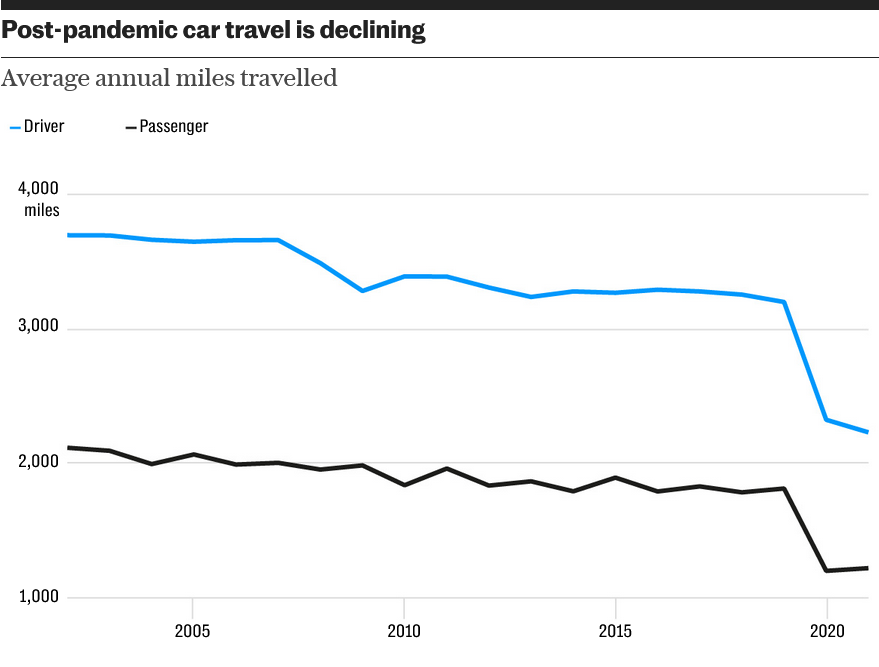

In Scandinavia, Smith says many Sixt customers go car-free in the summer when they take advantage of the warmer weather and use public transport or cycle, saving car hire for the colder, darker winter months. Driving may be slowly falling out of fashion. The distance travelled by car users was already in decline before the pandemic began. Between 2002 and 2019, the annual distance travelled by drivers fell by about 13pc, according to government data.

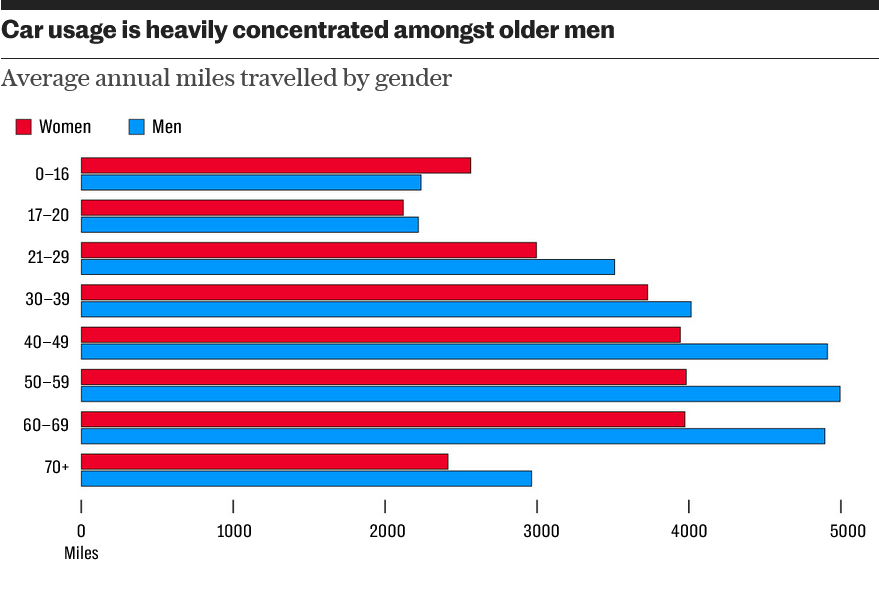

Naturally, this figure plunged in 2020 when the country was in lockdown. But it did not recover in 2021. It fell further. The distance travelled by drivers in 2021 was 40pc less than in 2002. The bulk of this travelling was done by people aged between 40 and 69.

“There is a steady decline because owning a car is getting more expensive,” says James Arbib, co-founder of RethinkX, a think tank. “Now, we are in a cost of living crisis, and we have more flexibility in how we work.” But all of these shifts are just the beginning of what will become an inevitable, wholesale overhaul of driving, says Arbib. Millennials and Generation Z are simply ahead of the curve.

“Autonomous vehicles will really unlock the end of car ownership,” he says. Currently, car sharing suffers from the same inefficiencies as bike sharing – namely that they get left in places where people do not need them, says Arbib. He believes self-driving cars will solve this problem.

This will be intertwined with the shift to electric vehicles. EVs have far fewer moving parts than traditional petrol cars and will therefore have much longer lifespans, says Arbib. “We expect that electric vehicles will have lifetimes of a million miles,” he says. This is around five times that of a typical car today.

“But a million miles of (a) lifetime is kind of useless if you own a car.” The average person travelled 2,229 miles by car in 2021, according to government data. A typical car owner will not benefit if their car has a longer lifespan, but they will still have to pay for it. In turn, driving will shift to a fleet-operated model, says Arbib.

“If you can split the upfront cost of the vehicle over a million miles or more, the cost drops dramatically,” he says, adding that the maintenance costs of EVs are also far lower. This will open up the prospect of a host of new business models. Companies operating car shares could monetise their services via advertising, sponsorship and data gathering rather than via fees, says Arbib. “You might see free transportation in cities.”

Of course, there is a major difference between urban and rural areas. The more dispersed the population, the less efficient alternatives to car ownership will be. But governments could offer subsidy programmes for less densely populated areas.

Sixt’s survey also reported high levels of attachment to owning a car. For many people, cars offer independence and comfort in a way that car sharing cannot. Can self-driving cars really override that?