In March, a man named Noland Arbaugh showcased his ability to play chess using only his mind, a remarkable feat for someone who has been living with paralysis for eight years. This was made possible by a brain implant designed by Neuralink, a company established by Elon Musk.

“It just became intuitive for me to imagine the cursor moving,” Arbaugh said during a live stream. “I just stare somewhere on the screen, and it would move where I wanted it to.” Arbaugh’s statement touches on a profound aspect of personal agency; he implies that he was the one moving the chess piece. Yet, this raises the philosophical query: was it really him, or the implant that executed these actions?

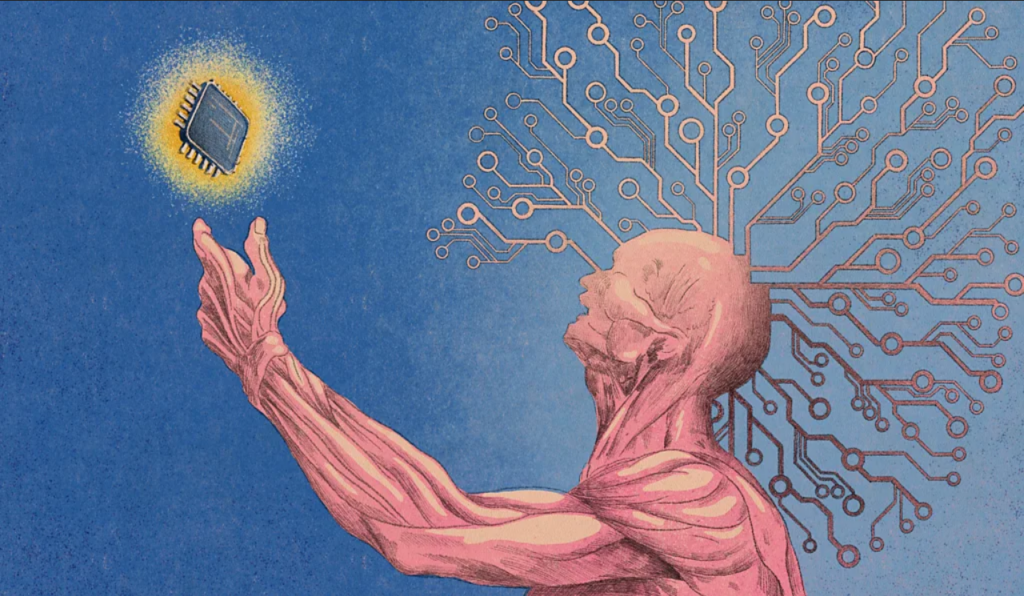

As a philosopher of mind and AI ethicist, this situation captivates me. Technologies like Neuralink’s represent a pivotal shift in the integration of the human brain with machines, prompting us to revisit our concepts of identity, self, and personal responsibility. While the immediate benefits for individuals like Arbaugh are clear, the broader applications could extend these implants to the general populace to augment their abilities as well.

This scenario brings to mind the extended mind theory, which has been a topic of debate among philosophers for decades: Where does our mind end, and the external world begin? Traditionally, one might assume that our minds are confined to our brains and bodies. Yet, in 1998, philosophers David Chalmers and Andy Clarke proposed a theory of active externalism, suggesting that technology could literally become a part of us. They envisioned a future where humans could delegate parts of their cognitive processes to external devices, effectively integrating these devices into our minds. This was before the advent of smartphones, yet it anticipated our modern reliance on technology for tasks ranging from navigation to memory storage.

If Arbaugh’s implant is not considered part of his mind, it poses complex questions about his ownership of his actions. Using Chalmers and Clarke’s ideas as a reference, Arbaugh playing chess involves him visualizing his moves—like moving a pawn or bishop—and his Neuralink implant picking up the neural patterns of this intent, decoding, processing, and executing the action.

Ownership of actions and personal agency become questionable in such scenarios. Normally, the gap between thinking and doing is non-existent. Consider Nora, a hypothetical woman playing chess without a BCI; her intentions and actions are seamlessly connected—she thinks, and then moves her hand. However, for Arbaugh, his intentions must be translated by the implant into actions.

This distinction introduces the contemplation conundrum: What happens if Arbaugh changes his mind in the split second after he forms an intent but before the implant acts on it? What if the implant misinterprets his deliberative thoughts as decisions? The implications extend beyond a game of chess. If such implants were to become commonplace, questions of responsibility for actions initiated by the implant would become increasingly complex. Could actions controlled by the implant feel alien, as if the device were intruding on the individual’s volition?

Moreover, the commercialization of such technology without adequately addressing these philosophical and ethical issues might lead to dystopian outcomes, reminiscent of William Gibson’s Neuromancer, where implants lead to loss of identity and manipulation. I propose revisiting Chalmers and Clarke’s extended mind hypothesis as a possible solution to bridge the gap between intent and action in individuals with brain implants. Embracing this view could help integrate the technology into the user’s self-concept, fostering a sense of agency and ownership.

Brain implants like the one used by Arbaugh are pushing the boundaries between the mind and machine further than ever before. This shift prompts us to reconsider our traditional views on identity, which have long been confined to the boundaries of skin and skull. As Chalmers and Clarke noted: “Once the hegemony of skin and skull is usurped, we may be able to see ourselves more truly as creatures of the world.”