Shoppers probably don’t think much about what happens next when they place an online grocery order. But it sets off an intricate dance of software, artificial intelligence, robots, vans, and workers. At an Ocado warehouse just outside Luton, the scene unfolds. As far as one can see, hundreds of robots whizz around a grid, fetching items for online orders. They move with dizzying speed and precision.

In the early days of online shopping, when an order was placed, humans would dash around a warehouse or a store collecting the items. But for years now, Ocado has been using robots to collect and distribute products, bringing them to staff, who pack them into boxes for delivery. And Ocado is not the only firm investing in such automation.

In its warehouses, Asda uses a system from Swiss automation firm Swisslog and Norway’s AutoStore. In the US, Walmart has been automating parts of its supply chain using robotics from an American company called Symbotic. Back in Luton, Ocado has taken its automation process to a higher level. The robots which zoom around the grid now bring items to robotic arms, which reach out and grab what they need for the customer’s shop.

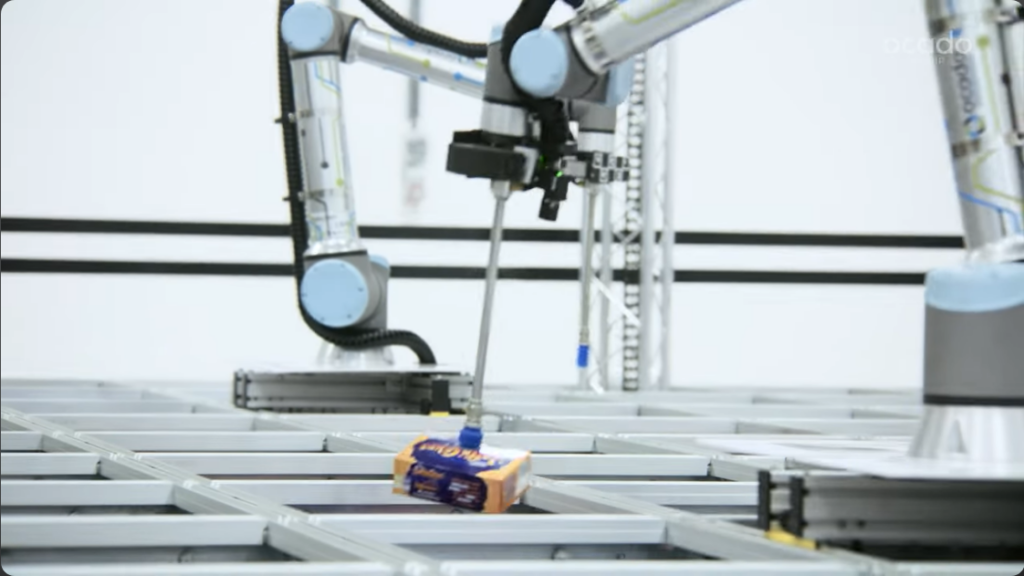

Bags of rice, boxes of tea, packets of crumpets are all grabbed by the arms using a suction cup on the end. It might seem like a trivial addition, but training a robot to recognize an item, grab it successfully, and move it, is surprisingly difficult. At Ocado, around 100 engineers have spent years training the artificial intelligence (AI) to take on that task.

James Matthews, chief executive of Ocado Technology explains the AI has to interpret the information coming from its cameras. “What is an object? Where are the edges of that object? How would one grasp it?” In addition, the AI has to work out how to move the arm. “How do I pick that up and accelerate in a way without flinging it across the room? How do I place it in a bag?” he says.

The Luton warehouse has 44 robotic arms, which at the moment account for 15% of the products that flow through the facility, that’s about 400,000 items a week. The rest are handled by staff at picking stations. The staff handle items that robots are not ready for yet, like wine bottles which are heavy and have curved surfaces, making them difficult to grasp. But the system is ramping up. The company is developing different attachments for the robot arms that will allow them to handle a wider variety of items.

“We’re just playing it carefully and ramping slowly over time,” says Mr. Matthews. “It’s a deliberate constraint on our behalf, so we continue providing good service to people, and not crushed custard creams in every order, or worse, putting stuff on the track that goes under the wheels of one of the bots and creates an incident.” In two or three years, Ocado expects the robots will account for 70% of the products.

This inevitably means fewer human staff, but the Luton warehouse still has 1,400 staff, and many of those will still be needed in the future. “There will be some sort of curve that tends towards fewer people per building. But it’s not as clear-cut as, ‘hey, look, we’re on the verge of just not needing people‘. We’re a very long way from that,” Mr. Matthews says.

Ocado is hoping to sell its automation technology to companies outside the grocery sector. Late last year it announced a deal with Canada’s McKesson, a large pharmaceuticals distributor. “Think about which industries have the need to move things around efficiently inside of a warehouse… it’s endless,” says Mr. Matthews.